塔里木胡杨林 Tarim Poplar Forest 84°11’35E-41°15’35N

彩色视频,声音; 水墨 矿物颜料 宣纸 Color Video, sound; ink and mineral pigment on paper

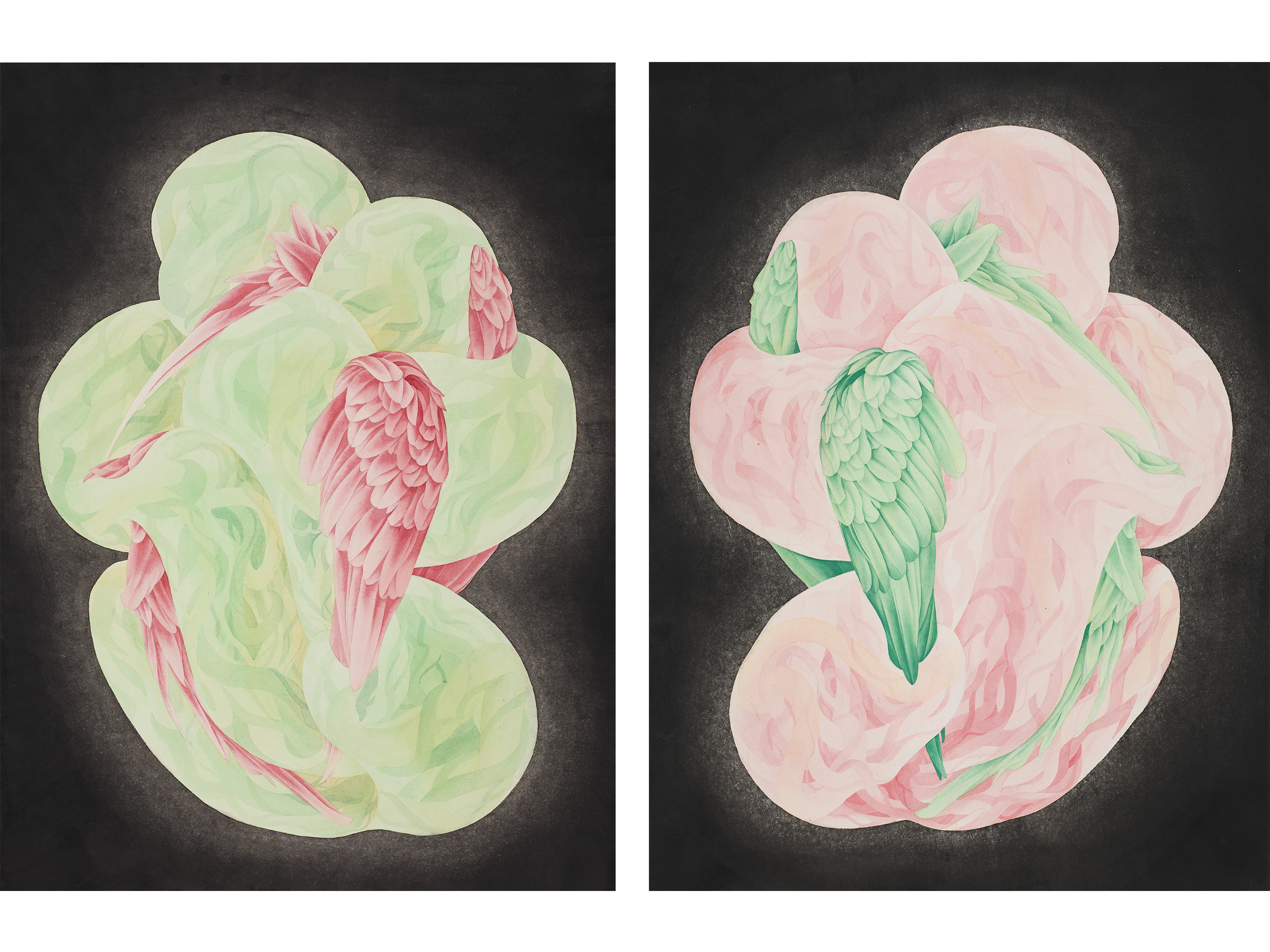

06’06”; 79 x 58 cm x 2

个体如何感知自我?如何找到自我的本质?没有什么特质后我就不再是我了?这些问题似乎可以通过环境不同所产生的相对关系和影响中有所感悟。胡杨在很多地方都有,但只有在新疆的这种特殊的干燥气候下才产生了‘三千年生命力’的传说和指代。成长背景的重要之处是慢慢理解周边的环境,以及它潜移默化带给我的想象力。

精神环境也是一样,《庄子》将枯木赋予了“材”的涵义,在阐述“不材之木”时指出枯树和人,并不一定是“不才之木”,只是处于“才与不才之间”,是对社会、人生态度的选择而已。因此,枯木被赋予了人生的选择、人世的态度。枯木的审美价不仅是物态形式上的,而且体现在情感中,超越了题材本身。而这种意象也是对于人生本质的追问。

绘画来自“物云云”系列。这个名字来自《庄子·在宥篇》:“万物云云,各复其根”。“根”是作为作品主要部分加以呈现的,繁复与缠绕自有其特殊美感。如看得见的如山川、血脉,亦如看不见的文脉与感受。

How does each individual perceive themselves? How to search for the essence of the self? Will I no longer be me if without certain qualities? These questions seem to be experienced and understood through the relative relationships and influences produced by different environments. The Euphrates poplar (Populus euphratica) trees can be found in many places, but it is only in the special arid climate of Xinjiang that the legend the poplar´s “three thousand years of vitality” has emerged. The significance of my background lies in gradually understanding the surrounding environment and feeling the imagination it subtly instills in me.

The same with spiritual environment. Zhuangzi assigns the meaning of cai, or “material” to deadwood and, when discussing the “wood that cannot be used as material,” points out that dead trees, as well as people, are not necessarily “unusable wood,” but are simply in a state between “being fit to be useful and wanting that fitness,” in other words, contingent upon a choice of attitude towards life and society. Therefore, “deadwood” is endowed one´s choices in life and one´s attitude towards the world. The aesthetic value of dead trees is not only in their physical form but also in human emotions, transcending the subject itself. This imagery is also an inquiry into the essence of life.

The painting chosen for this location is from the Root of All Life series. The name “Root of All Life” comes from the chapter “Letting Be, and Exercising Forbearance” in the Zhuangzi, which says “of all the multitude of things, every one returns to its root.” The “root” is presented as the main part of the painting—whose complexity and entanglement bears its own special sense of aesthetic beauty—as visible elements like mountains, rivers, blood vessels, and lightning, and as invisible elements like cultural context and feelings.